www.snohomishwomenslegacy.org |

WLP Story Number 74

LILLIE CORDELIA (NAIRN) BREED ~ Pioneer in the Wilderness

By Betty Lou Gaeng

Lillie Cordelia Breed was one of those hardy pioneers who tamed a

wilderness. She died several decades before her land and the community

of Alderwood Manor became part of the prosperous city of

Lynnwood. However, Lillie left a legacy—a legacy unknowingly used

and appreciated by many people in our day. Even Lillie Breed

would be surprised at the everyday happenings on what was her

land. Before learning about the legacy though, let’s get to know

more about Lillie herself.

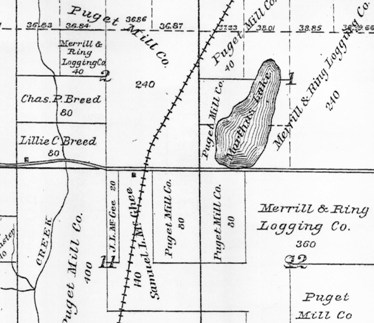

During the late 1880s, many years before Puget Mill Company began the

harvesting of its company-owned forest land in south Snohomish County,

and their later platting of this property into small farms, a few hardy

pioneering homesteaders had already settled amid the huge trees.

One such family was that of Lillie and Charles Breed and their

children. The Breeds filed their homestead claim in 1888 with the

Seattle office of the Bureau of Land Management for 160 acres of timber

land in south Snohomish County, a few miles east of Puget Sound.

Following a cash payment of $200 ($1.25 per acre), a land patent was

issued on June 18, 1890. In 1934, the Edmonds Tribune

Review, the newspaper for south Snohomish County, published on its

front page a lengthy and detailed account of the life of Lillie Breed,

calling her a pioneer woman of Alderwood Manor who had seen the west

grow from a wilderness.

Lillie Cordelia Nairn was born in Monterey, near Batchtown, Illinois,

December 12, 1856. Lillie came from a family whose roots were

traced far back—one with a very prominent and colorful history.

Her southern paternal grandmother, because of her Spanish ancestry, was

given a land grant where the city of Saint Louis now stands.

However, when the land became part of the United States, it was lost to

the family. Lillie’s paternal grandfather’s roots were from the

very old Nairn family of Scotland.

When Lillie was a small child the Civil War erupted and her father,

John Nairn, organized and became captain of a volunteer regiment of

young men for service in the Northern Army. After her father’s

return from the war, the family lived on their large farm in Illinois,

and even though she was not a healthy and robust girl, Lillie had a

great love for the outdoors. In her younger days, horseback

riding was her greatest pastime—usually riding sidesaddle.

When Lillie’s father died in 1874, her mother decided to move the

family west from Illinois to Kansas to seek a new home where Lillie’s

health might improve. Traveling by covered wagon they settled in the

prairie country near Pawnee Rock, Kansas, and took up grain farming as

a livelihood. It was in Kansas that Lillie met her future

husband, Charles Bradley Breed. They were married in 1881.

Times were hard in Kansas and shortly after their marriage, they

traveled west by wagon train to Ratoon, New Mexico, a lawless-pioneer

town where hangings and gun fights were commonplace. Charles worked as

a laborer for the Santa Fe Railroad and Lillie worked in the railroad’s

cook house.

After spending about a year

in New Mexico, Lillie and Charles realized this was not the place

to raise a family, so they returned to Kansas to again try farming and

begin their family. In Kansas, three children were born to them,

Laura Fern (1882), John Amos (1884) and Ethel Mary (1886). Facing

lack of rain, dust storms, crop failures and a depressed economy,

farming in Kansas became a disaster for the Breeds. The Call of

the West and a better life for the family was what Lillie and Charles

chose. Packing their belongings and saying good-bye to relatives

and friends, with their three small children in tow, Lillie and Charles

headed west to Washington Territory by train, an adventure in

itself. They were on the Northern Pacific passenger train that

went over the “switchback” in the Rocky Mountains. There was no

railroad bridge over the Columbia River, thus from Portland the train

was floated across on a ferry. The train then traveled to the

railroad terminus at Tacoma, and from there they took a small steamer

up Puget Sound to Seattle.  In Seattle, Charles Breed worked as a carpenter, and

he applied for the 160-acre timber claim near Martha Lake in south

Snohomish County. Twins, Flora Pearl and Paul Nairn, were

born in 1888. However, Paul died young and was buried in

Seattle. Still in residence in Seattle, Lillie and her family

witnessed the great Seattle fire in 1889, and the birth of the State of

Washington. While living in Seattle and then Stanwood, Charles worked

to make their homestead livable for the family. By this time

there were five children. The youngest, Bessie Alice, was born in

Stanwood in 1890. Lillie and Charles decided it was now time to

move to their new home.

In Seattle, Charles Breed worked as a carpenter, and

he applied for the 160-acre timber claim near Martha Lake in south

Snohomish County. Twins, Flora Pearl and Paul Nairn, were

born in 1888. However, Paul died young and was buried in

Seattle. Still in residence in Seattle, Lillie and her family

witnessed the great Seattle fire in 1889, and the birth of the State of

Washington. While living in Seattle and then Stanwood, Charles worked

to make their homestead livable for the family. By this time

there were five children. The youngest, Bessie Alice, was born in

Stanwood in 1890. Lillie and Charles decided it was now time to

move to their new home.

Leaving Stanwood, the family landed at Mosher

(now Meadowdale), a flag station four miles east of Edmonds.

Heading for their home, with wagons loaded with children, clothing,

household goods, food and grain, and herding their cows, the family

traveled east over a narrow trail through a wilderness with trees so

thick and tall that very little light penetrated the darkness.

The forest abounded with wild game, and fowl, and the streams with

trout, and salmon in season. Lillie and Charles named their new

home Ruby Ranch, and except for two years when the family lived at Lake

Ballinger working a sawmill they owned, Lillie and Charles lived on

their ranch, raising their family, building a larger home, and taking

an active part in the development of a new community .

Lillie Breed never became strong and robust like most

pioneer women. However, as her family said, she had grit and courage.

She witnessed a lot of changes in her lifetime. She saw both Seattle

and Everett grow from small villages to cities. Before her death,

Lillie was a witness as the uninhabited wilderness around her own home

developed into a community of some fifteen hundred families.

Those who came later owe a debt of gratitude to the early settlers such

as Lillie and her family—their pioneering spirits and hard work cleared

the way.

Lillie and Charles Breed

celebrated their golden wedding anniversary September 1, 1931.

Loaded down with well-filled picnic baskets, a vast number of relatives

and friends gathered for the occasion at nearby Martha Lake.

Lillie Cordelia Breed died at the age of 78, just two days before

Christmas in 1934. She left behind a large family, many friends,

and the history of a life well-lived. She is buried in Edmonds at

Edmonds Memorial Cemetery. Her husband and four of her children, Fern,

Ethel, Bessie and John survived her. Charles Bradley Breed died

in 1946 at the age of 93, and is buried beside Lillie.

Lillie’s life and home are memorialized in a way little known to most

people—it is her legacy to the people of Lynnwood. Her pioneer

land is visited by dozens of people every day of the week. If you

drive along 164th Street Southwest in today’s Lynnwood, near the Swamp

Creek Interchange, a couple of miles west of Martha Lake, you will be

passing by the south end of what was Ruby Ranch, long-time home of the

Breed family. The modern scene shown in the accompanying photo is

one repeated each day at the big dip in the road, on land that was once

belonged to Lillie. What appears to be never-ending water

flows from the pipes of an artesian well that graces Lillie’s old

homestead land. Vehicles of all kinds stop at this spot at all

hours of the day.  With

containers of varying shapes and sizes in hand, people come from as far

away as West Seattle to wait in line to fill their containers with

water that is cold and crystal clear, with no taste of chemicals.

Surprisingly, in our present day when almost everything is a commercial

enterprise—the water is free to all—managed and inspected by the local

water district. The next time you fill your jug at the 164th

Street watering hole in the Lynnwood of today, remember Lillie and her

hard work to help carve out a home for her family in the

wilderness.

With

containers of varying shapes and sizes in hand, people come from as far

away as West Seattle to wait in line to fill their containers with

water that is cold and crystal clear, with no taste of chemicals.

Surprisingly, in our present day when almost everything is a commercial

enterprise—the water is free to all—managed and inspected by the local

water district. The next time you fill your jug at the 164th

Street watering hole in the Lynnwood of today, remember Lillie and her

hard work to help carve out a home for her family in the

wilderness.

| Before her own death in 1973, Bessie Alice (Breed) Cornell, Lillie and

Charles’ youngest daughter, narrated the history of the family, as well

as stories of their struggles and adventures in the wilderness.

Bessie’s daughter, Betty Alys (Schoppert) Morgan, collected and typed

her mother’s stories and these are part of a collection which will soon

be housed at the Heritage Resource Center, Alderwood Manor Heritage

Association, Heritage Park, Lynnwood. One of these stories tells of the misadventure which caused Lillie to walk with a limp from her early days at Ruby Ranch, and for the rest of her life. This is the story: “Five Bullets for a Christmas Present, but Only One Struck Home.” Shortly before Christmas, Lillie decided to walk to a neighbor’s house, two miles away, to visit with her friend Elizabeth Morrice [where the Alderwood Mall is located in our day]. The day was sunny, clear and sharp—a beautiful day for a stroll in the woods. Lillie stayed longer than she had intended and darkness fell before she made it home. Unknown to her, a neighbor boy and a friend visiting him decided to go hunting on the timbered side of the swamp. The boys got lost but finally came to Swamp Creek on the west and safe side of the swamp. In the darkness, they decided it was best to follow the creek, which they knew would take them by the Breed ranch. As Lillie was nearing her home, with about a fourth of a mile still to go, the boys reached the road and were scared half to death by what they saw. Lillie was wearing a dark full length cape, with a black scarf tied over her head. She was coming down the hill in a hurry to get home—her cape waving in the breeze. The boys going up the hill were startled when they saw the movement of the cape and fired five shots at this terrifying figure; one from one gun and four from another. When the two boys heard Lillie scream, “I guess you are trying to kill me,” as she fell behind a log lying beside the road, they realized what they had done and ran up to where she was lying. One of the boys hurried to the nearby Breed house for help while the other boy ran to the Morrice place. William Morrice, Jr. went another four miles west to Harry Reid’s place and sent him to Edmonds for Dr. Smith. Mr. Breed hitched up the horse to a sled and he took Lillie to their house. Luckily, the bullet hit Lillie in the instep just as she was taking a step and it came out through her heel. Dr. Smith took care of the wound until it finally healed. The boys who did the shooting paid the doctor’s bill, but they could never repay Lillie for her pain and suffering, nor her years on crutches and cane, and the pronounced limp she endured for the remainder of her life. |

Sources:

Pioneer Woman Dies in District, Mrs. Lillie Nairn Breed of Alderwood Saw West Grow From Wilds, Edmonds Tribune-Review, Edmonds, WA; Friday, December 28, 1934, Page 1. From the collection of original Edmonds newspapers located at the Sno-Isle Genealogical Society Research Library, Heritage Park, Lynnwood, Washington.

A reproduction of a copy of the original land patent No. 11602 to Charles B. Breed issued 6/18/1890 for 160 acres in Snohomish County, WA, on file in the Office of the Bureau of Land Management, Oregon State Office, Portland, Oregon.

Quit Claim Deed, Charles B. Breed to Lillie C. Breed, Sept. 11, 1903; Vol. 80, Page 275, Snohomish County, WA for 80 acres.

Collection of family stories narrated by Bessie Alice (Breed) Schoppert-Irby-Cornell (1890-1973) and documented by her daughter, Betty Alys (Schoppert) Morgan (1925-1997) — presently in the possession of the author.

Anderson Map Company, and James W. Myers. Plat Book of Snohomish County Washington. Seattle, Wash: Anderson Map Co, 1910, p. 7.