www.snohomishwomenslegacy.org WLP Story # 55 ~ |

Lillian Sylten Spear ~ Public Power Advocate

By Margaret Riddle

Her Early Years

Lillian E. Anderson Sylten Spear was an important player in Snohomish County’s public power movement. An educator and persuasive speaker, she once told the press that she loved tackling issues that helped to better democratize her community. Public power sparked her interest, a cause supported by the Washington State Grange. Lillian began working for the Grange in 1936 and never looked back.

Lillian was born in Portland, Oregon on July 26, 1897 to Norwegian immigrant parents Oline Mahlen and Alexander Anderson and was next to the youngest of thirteen children. In the early 1900s the Andersons moved to Everett where Lillian attended city schools. She earned a teaching certificate from Ellensurg Normal and worked as Principal of Silver Lake Elementary, which is now part of the Everett School District. Already married by this time, Lillian was able to serve as a school administrator but would have been discouraged from teaching as a married woman. Wed in 1920 to Arne Sylten, a lumber inspector, the couple had three daughters, Olene, Daphne and Joann. This marriage eventually ended in divorce. Lillian remarried in 1944, this time to Harrison George Spear, a marriage that lasted five years.

Public Power for Snohomish County

Passage of the Washington State Grange Power Bill on November 4, 1930 spurred action to create public power districts in those areas that had not already done so. With the 1932 election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and public power advocate Homer T. Bone as Washington State Representative, the state seemed ready for public utility ownership. Both Grant and Spokane counties created public utility districts that year.

Snohomish County’s struggle took longer. Puget Sound Power

& Light had organized a farm electrification department in

1924 and, despite high and unfair rates, they dominated

Snohomish County.  The Grange aggressively opposed

Puget Power’s hold and placed a measure on the 1932 ballot

to create a Snohomish County public power district. But

ten Snohomish County mayors and the Everett Herald,

worked to defeat the initiative. Herald editorials

warned that the law would give PUD commissioners power to

condemn and confiscate property, thus reducing tax revenue.

An organization called the Snohomish County Tax Reduction Association

implied that this measure was an effort to seek public

payroll jobs. Underlying their opposition was a fear of

socialism or, as some perceived it, communism. The measure

was defeated by a two-to-one margin.

The Grange aggressively opposed

Puget Power’s hold and placed a measure on the 1932 ballot

to create a Snohomish County public power district. But

ten Snohomish County mayors and the Everett Herald,

worked to defeat the initiative. Herald editorials

warned that the law would give PUD commissioners power to

condemn and confiscate property, thus reducing tax revenue.

An organization called the Snohomish County Tax Reduction Association

implied that this measure was an effort to seek public

payroll jobs. Underlying their opposition was a fear of

socialism or, as some perceived it, communism. The measure

was defeated by a two-to-one margin.

Above - The Tri-Way Grange in Silver Lake

The federal government’s creation of the Grand Coulee Dam in Eastern Washington and the Bonneville Dam near Portland gave momentum to organize for public power since public utility districts were given priority to receive electricity generated from the two facilities. With this incentive, Snohomish County PUD was formed by county vote in 1936. But the struggle to acquire Puget Power’s Snohomish County properties—so that the district could begin selling electricity—continued for over a decade.

Becoming Involved

Lillian adult life began as a mother and an educator. In addition to serving as the Silver Lake Elementary principal, she was also president of the Snohomish County Parent-Teacher Association (PTA). Her organizational skills quickly led her to a position on the PTA’s state board. Lillian also worked actively in the Democratic Party but it was the Grange and their support of public power that interested her most. In a newspaper article Lillian stated that she had to learn about public power. At the start she still cooked on a wood range and didn’t even have a refrigerator. But Sylten soon was a knowledgeable spokesperson. In 1936 she ran for Public Utility Commissioner and, although she did not win, her name became known. She quit her job as school principal to actively work for public power. From 1940 to 1946 Lillian served as District Auditor for the Snohomish County PUD.

She became an influential public speaker and in 1941 told a reporter:

“We had two bad years when our county was pointed to as a bad example. We had inefficient commissioners. The only way we could educate people about the power projects was to go out and talk to them and answer their questions. That was my work.” (Spear, Seattle Post Intelligencer)

Everett Herald editor and publisher Gertrude Best was an outspoken opponent of public power. Without Herald support, the Grange relied on speaking campaigns. Lillian spoke to clubs and organizations, particularly taking the message to Snohomish County women. She also helped organize distribution of literature and when it came to fundraising, she often simply passed the hat. In telling her story later to historian Richard Berner, Lillian recalled her battles with Gertrude Best, saying that the only time she received front-page coverage in the Everett Herald was when she was ticketed for speeding. The headline had read: “Mrs. Sylten Arrested”.

More Organizing

In 1939 Snohomish County PUD joined six other Washington State public utility districts to buy Puget Power. Lillian Sylten became secretary of the negotiating group named the Puget Sound Utility Commissioners’ Association (PSUCA). The group soon realized that Puget Power was not bargaining in good faith and were attempting to stop the buyout. A Washington Public Ownership League (WPOL) was formed and Sylten became its secretary.

Negotiations stalled then were renewed many times in efforts to establish a fair price. Snohomish County PUD joined other PUDs in filing a condemnation procedure against Puget Power. Boxes of Lillian S. Spear material in the University of Washington’s Special Collections attest to her involvement in Initiative 12, sponsored by the WPOL. Passed by the legislature, the initiative allowed for joint suits by PUDs. Lillian also supported Referendum 25 which put the measure to public vote in 1943. But by this time factionalism was developing among the ranks of public power advocates. Some disliked the WPOL for their socialist bias. Sylten—a Democrat, not a Socialist—served as the president of the Women’s Committee for Referendum 25. She wrote articles in favor of the measure in Public Power News, a journal issued by the WPOL. Referendum 25 was narrowly defeated. Now with no joint suit possibilities, the PSUCA once again became active.

Squabbles continued to divide public power advocates and

Lillian (now Spear) became disenchanted with the movement

and resigned in 1947, two years before publicly owned power

truly came to Snohomish County on September 1, 1949.

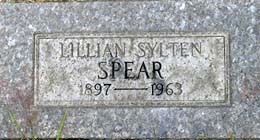

Lillian Sylten Spear moved to Santa Rosa, California in 1953 where she continued her activism working to rid the state of pollution. In her final years, she struggled with bone marrow cancer and died in California in 1963 at 66 years of age. A plain headstone marks her grave in Everett’s Evergreen Cemetery.

Sources:

Wendy Brush, “Lillian Sylten

Spear, Outspoken Advocate of Public Power”, University of

Washington Women Studies Class 283, December 12, 1984,

Lillian S. Spear files, Everett Public Library;

“Biographical Note”, Guide to the Lillian S. Spear Papers

1931-1963, University of Washington Manuscript

Collection No. 0381; Boxes 2, 5 and 7,

Lillian S. Spear Papers, 1931-1963, University of

Washington Manuscript Collection No. 0381;

“Woman Is a Power In P. U. D. Movement”, Seattle Post

Intelligencer, February 26, 1941.