www.snohomishwomenslegacy.org |

Snohomish County Women and the 1910 Suffrage CampaignBy Margaret Riddle and Louise Lindgren |

|

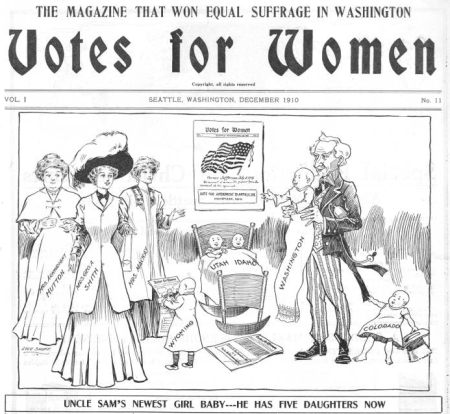

Votes for Women, Vol 1, no. 11, December 1910 |

On November 8, 1910, Washington State’s male voters passed the

women’s suffrage referendum by a majority of almost two to one, making

Washington the fifth state in the nation to enfranchise women. But in that year Washington women

were really winning back their vote. When Washington

was a Territory, women could vote, but only from

1883 to 1889. Women had backed reform closing down saloons and brothels. Through taxes and licensing these businesses were the mainstay of funding for many towns and cities. Thus suffrage was considered “bad for business.” Under pressure, the State Supreme Court cited a technicality making equal suffrage illegal. That, along with a strong saloon lobby, brought Washington into statehood in 1889 without women’s suffrage. For this reason, 1910 Washington suffragettes distanced themselves from the liquor issue, even though many strongly supported prohibition. |

Winning the vote for women in Snohomish County

Snohomish County women were prominent in the 1910 campaign. A major player was Mrs. M. T. B. Hanna (1856-1926) of Edmonds. Missouri Hanna edited and published Votes for Women, the official organ of the Washington Equal Suffrage Association. The publication ran from 1909 to 1910 combining news from suffrage clubs throughout the state, editorials, cartoons and political commentary. When the vote was won, the paper continued through 1912 as The New Citizen, focusing on women’s issues.

| Missouri Hanna was not new to

journalism in 1910, having founded the Edmonds

Review in 1904, the year she moved to Edmonds. She

had been widowed and turned to journalism in order

to support herself and two daughters. Her passionate

and articulate support of women’s causes led her to

publish Votes for Women. In Hanna’s words: “It is argued that, given the ballot, women will cease to care for the home, leave the meals uncooked, the children uncared for, the buttons strewn while she rushes off to vote. As it only takes about two minutes to perform the function of voting none of the above calamities are likely to happen. We venture to guess that the enfranchised woman can cook and serve a delicious dinner, sew on the buttons, and kiss away the children’s tears with the same degree of success and womanliness that she can stand and hang to a strap in the crowded street car while her brother man sits comfortably, reads his paper contentedly and puffs tobacco smoke in her face, serenely oblivious of her presence.” Hanna’s publication gives glimpses of other Snohomish County suffragettes. Some were prominent teachers such as Mary McNamara, president of both the Snohomish County and Edmonds Equal Suffrage Clubs and Rainie A. Small, a teacher in the Snohomish County schools for fourteen years. Small was also county superintendent of schools in 1900, principal of Florence and Edmonds High Schools and a pioneer worker for the Grange. |

|

|

The Everett Suffrage Club Everett was a strong center for labor and labor supported the suffrage cause. Voting support was needed to provide decent working conditions, safety regulations and the eight-hour day demanded by workers. It was also in the interest of working men to avoid competing with women who were usually hired at a lower rate of pay. If women could vote there might be a chance for labor’s long-sought “equal pay for equal work.” In the September issue of Votes for Women, Hanna wrote that the Everett Suffrage Club had been one of the most successful in the state at gaining press coverage. The club was featured regularly in the Everett Daily Herald, the Everett Morning Tribune and the Labor Journal, thus reaching thousands of readers. Operating from a third-floor room in the new Commerce Block in Everett, suffrage club members strung a large, conspicuous yellow banner across Hewitt Avenue before election day with the legend “Vote for Amendment, Article VI: It Means Votes For Women”. Since the official ballot did not include the words “Woman Suffrage”, suffragettes felt they needed to educate voters on how to mark their ballots. |

|

|

Dr. Ida Noyes McIntyre, M.D. (1859-1932) was the Everett club’s Vice President. She had come to Everett in 1901 to practice medicine and set up a clinic. A dedicated suffragette, Ida had helped win the vote for women in Colorado. She opened her clinic for meetings of the Everett Suffrage Club.

A colorful event captured front-page attention in both of Everett’s daily newspapers. On July 5, 1910, Ella M. Russell, president of the Everett Suffrage Club, rose to her feet before sixty-five hundred people in a Billy Sunday crusade in Everett to answer an attack on women’s suffrage. The attack came from Mrs. Rae Muirhead, a Bible speaker with the Sunday campaign. Mrs. Muirhead opposed women’s suffrage and in her testimony that evening said that a woman’s role was to teach her sons to vote properly. She also claimed to have received harassing letters from the Everett Suffrage Club. Ella Russell asked to be heard and when denied, stepped up on a bench in front of the hall and began to speak. Mrs. Muirhead, Ella explained, was a woman of influence. The suffrage club had written only in hopes of gaining her support. Reporting this event in Votes for Women, Missouri Hanna wrote: “This event became the rallying point of an enthusiasm for suffrage which has put Everett in the forefront of the campaign. Mrs. Russell is resourceful, she has rallied about her many able women and many novel schemes have been devised to further the cause of suffrage in Snohomish and adjoining counties.” |

| Mrs. Muirhead was

not alone in her thinking. Many prominent women were

against women’s suffrage citing passages from the

Bible which placed women under the authority of men

and predicting the downfall of the family and loss

of women’s special “privileges and position” in

society. The Everett Suffrage Club spoke to these

women in the Labor Journal of November 4, 1910: “IF

YOU WERE A GIRL WORKER: “No woman in silks and

satins, whose only care is how she may keep her

social light burning brighter than her rival’s has

any right to stand in the way of the rights of the

woman who toils.” And regarding widows with children

who often lost not only the breadwinner but their

inheritance when death intruded, the writer

continued: “No woman, whose home interests are well

cared for, has any right to stand in the way of the

rights of the woman who has carried her mate to the

grave.” This plea was before social “safety nets”

such as Social Security! The Vote is Won

The 1910 suffrage campaign was well organized. This time Washington women won the vote and kept it. Speaking at a victory party, Dr. Ida McIntyre expressed her delight with the win but also stated that she felt running for office would still be years away. Ten years later, August 26, 1920, the 16th Amendment to the Constitution gave women the right to vote nationwide. |

|

National American Woman Suffrage

Association, and Washington Equal Suffrage Association.

Votes for Women. Seattle, Wash: M.T.B. Hanna, 1909.

[various issues] Accessed via UW

Libraries Digital Collections Pamphlets and Textual Documents

Collection, Washington Equal Suffrage Association "Votes for Women"

Everett Trades Council, Everett Central Labor Council

(Wash.), and American Federation of Labor. The Labor

Journal. Everett, Wash: Everett Trade Council, 1909.

[all issues]

Louise Lindgren,

“To Vote or Not Vote: That Was the Question,” The Third

Age News and Information for Contemporary Seniors August 1995.

[Senior Services of Snohomish County. Mukilteo, WA., 1990s]

The Everett Daily Herald. Everett, Wash: [s.n.],

1897.