www.snohomishwomenslegacy.org WLP Story # 42 ~ |

|

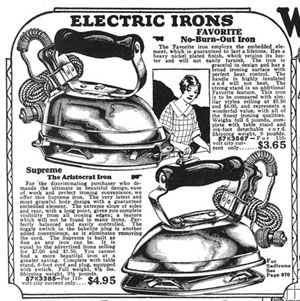

Grace DeRooy VerHoeven: An Everett ChildhoodBy Phyllis Royce “Housework is so much

easier here. “ Clazina DeRooy wrote in a letter to

her family in Holland. “Almost everyone has

electricity.” It was 1926 when Clazina, her husband and their six children first arrived in Everett. Although the new house did indeed have electric lights, it lacked the other labor-saving electrical appliances she had heard so much about. According to her daughter, Grace, her mother’s first electrical appliance was an iron. Wrinkle free ‘wash and wear’ fabrics did not yet exist. Clazina, like other respectable homemakers, had, until that time, pressed almost every article of her family’s clean clothes with a heavy flat iron that had to be continually reheated on her wood stove. Her new appliance was light enough for a child to use, and it heated itself with the flick of a switch. |

|

||

|

|

My nine brothers

and sisters and I all had our jobs. As we grew, we

progressed to various duties. We enjoyed and begged

to do them when we were little, but when the work

became a regular assignment, the novelty quickly

wore off. |

By the time we were seven or eight, we were

helping with the annual spring cleaning and with the

canning, taking peas out of pods, looking for worms, taking

strings off the beans, shucking the corn, peeling and coring

apples, etc. And always, Mom was around and on top of what

we were doing....

Spring housecleaning began the day school was out. It meant

completely emptying every room, stripping it of bedding,

curtains, pictures....even the clothes from the closets. We

washed what could be washed, including walls and woodwork

and ceiling. We painted and varnished and wallpapered, as

necessary and affordable. We never had a vacuum cleaner, so

we took the living room rug— $3.00 at the Salvation Army—out

to the yard and hit it with sticks. We cleaned the ceilings,

beat the mattresses and the pillows and sometimes changed

the ticking, washed blankets, furniture and bedsprings

(which at the time were bare metal) —and then replaced

everything where it belonged.

The work went on for two or three weeks, usually one room a

day. Everyone was assigned chores. The boys moved the

furniture and mattresses, carried ladders, took the beds

outside, things like that; the girls washed and polished and

remade the beds. I always thought that the boys had it a

little easier than the girls, though the boys carried wood.

We burned a lot of wood. Spring cleaning was usually

completed—sometimes interrupted for a day or two when fruits

ripened early—just in time for the jam and jelly making and

summer canning.

When I was twelve in 1938 (the older girls were now in

junior and senior high school), I inherited the

responsibility of hurrying home at lunch time on Mondays to

help hang out the laundry. Before the boys left for school,

they would have helped carry the double boilers of hot water

from the stove to the back porch and poured it into the

washing machine and the large round tubs used for rinsing

and bluing (bluing is a mild blue dye which counteracts the

cream/gray color in white cloth).

Mom began the laundry early, and two large baskets were

usually ready and waiting. After a very quick lunch of

either cocoa and dried bread crusts or fried potatoes and

rhubarb sauce or applesauce, I was in the yard, wiping the

fine gray residue from the mills off the clotheslines with a

damp cloth.

Mom would not permit haphazard hanging of the laundry. We

hung the sheets together on the outside lines on either side

of the yard. Towels, shirts and dresses hung on inside

lines, and underclothing was hung on the very middle, far

away from prying eyes. I figured our neighbors had more to

look at than our clothesline, but it was important to Mom

that our laundry look as neat as possible to the neighbors.

She was always careful about appearances.

With all this work, our house should have been spic and

span. It wasn’t. But if it wasn’t neat, it was clean. With

twelve people in the house, Mom did a remarkable job,

especially without many electrical appliances. Of course she

was home all day and had ten lackeys to do her bidding. But

she must be given a good deal of credit for supervising ten

apprentices and keeping us as organized as she did.

Religion was another important aspect of the DeRooy family’s life. Grace’s parents, Arie and Clazina, joined the Christian Reform Church immediately after they arrived in Everett. The entire family attended both morning and afternoon services on Sundays, Arie read to them from the Bible after supper, and the children attended Saturday catechism.

We were taught by example that life’s most important institution after family, is the church. We might misunderstand; understanding it, we might become angry with it, but we didn’t take it lightly. The entire family was active in the church.

We often congregated in the living room on Sunday to sing hymns as Tina (one of Grace’s sisters) played the piano. We also sang popular songs, but had to be selective to avoid Mom’s coming in and quietly but decisively picking up the piece and placing it aside or closing the piano. She liked to sing and often joined us, but to her, some songs were appropriate for Sunday, some were not.

Women were not permitted to vote in church matters, but were active in the Ladies Aid and undoubtedly advised their husbands in church matters they did know about. Church matters were often discussed at home, but kindly. We did not “serve up” the minister for Sunday dinner.

Movies were strictly forbidden, except for those offered free by local merchants just before the beginning of the school year. The ‘back to school’ movie was usually a cowboy movie and a cartoon—not something guaranteed to lead us down the path to sin. Ice cream was forbidden on Sunday, “verboten op Sundog”, and we were not allowed to play cards. I don’t think we had a lot of time to play games except during long summer evenings when we played out in the street with the neighbor kids.

|

At the end of our block stood a Roman Catholic Church, “Our Lady of Perpetual Help”, and the Catholic school. We played with our Catholic neighbors, but at times we would bicker, throw mud at each other and call each other names—never, of course, in our parent’s hearing. It had nothing to do with the difference in religion—it was just that we were different. We were Dutch; the Soriano family across the street, with almost as many children as ours, was Italian. They were recent immigrants, too...vocal and demonstrative.... Had it not been for the law, there would have been serious altercations at times. A final thrust at the end of a disagreement, always first checking carefully to see whether Dad or Mom was within hearing was our catcall: “If you ain’t Dutch, you ain’t much.” |